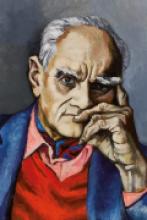

A brief introduction to Brian Eno’s generative music

by Michael Bracewell

Brian Eno’s generative music systems are best known for creating richly textured soundscapes, as engrossing as they are minimal, and as densely layered as they are refined to delicate curves, drifts and traceries of sound.

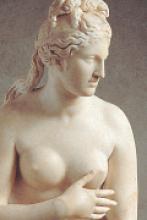

His collaboration on Mimmo Paladino’s sculptural installation, collectively known as I Dormienti, and first shown at the Undercroft of London’s iconic ‘The Roundhouse’ venue in the early autumn of 1999, marked a simultaneous advance and consolidation of Eno’s career- long fascination in music making systems; more specifically in the routing of generative music through notions of time, randomness and context.

In this, his interest in the generative became on one level an enquiry into the passing of time.

The idea of creating music generating systems has been central to Brian Eno’s art and ideas since his days as a student at Winchester School of Art, during the middle years of the 1960s. Famously, Eno has cited Steve Reich’s pioneering work from 1965, It’s Gonna Rain – in which a tape recording of a Pentecostal preacher’s sermon is played back in semi-sampled form at differing speeds – as being hugely influential on his thinking. But Eno’s development as an ideologue, ‘non-musician’ and artist has always been founded upon an astonishing configuration and conflation of at times seemingly irreconcilable enthusiasms. Indeed, it is out of precisely such a fusion of opposed ideas, and Eno’s ceaseless questioning of the subsequent evolution of this fusion, that his originality, intellectual nerve and creative restlessness has emerged.

Eno’s earliest involvements with generative music embrace both the landscape of progressive rock and the enquiries of the British classical avant garde. Back in 1968, with a fellow student from Winchester School of Art accompanying him on guitar, Eno had ‘played’ a signals generator - essentially a device for testing laboratory equipment, and almost entirely imprecise as a musical instrument. A little later, during the closing years of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s, Eno had become an enthusiastic member of both The Portsmouth Sinfonietta and The Scratch Orchestra. These were music making groups comprised of players with hugely differing ability ranges, the consequent performances by whom - when following a score - became as unpredictable as they were intuitively poetic, their pursuit of musical coherence being likened by Eno to the patterns of ‘flocking behaviour’ in birds.

Both of these formative experiences of music making would advance Eno’s interest in the relationship between systems and chance - a fascination which would evolve through his work during the 1970s to achieve consumate elegance (although no conclusion) in his legendary release of 1975, Discreet Music.

In the opening remarks of his sleeve note for this recording, Eno summarised his early thinking on generative music: “Since I have always preferred making plans to executing them,” (he wrote) “I have gravitated towards situations and systems that, once set into operation, could create music with little or no intervention on my part. That is to say, I tend towards the roles of planner and programmer, and then become an audience to the results.”

The generative music system created by Brian Eno nearly fifteen years later for I Dormienti is in the direct lineage of this founding statement, its conceptualism both refined and enhanced by subsequent developments in technology and the progression of Eno’s thinking. By applying the lush, meditative, compositional aesthetics that he had honed to such masterpieces of musical

minimalism as Thursday Afternoon (1985), to the processes of randomness and longevity enabled by CD technology, Eno created a system of unpredictable overlay which, as he wrote of I Dormienti in 1999, enabled a total playing time that was “effectively infinite.”

The holistic nature of Eno’s creativity, and the manner in which he allows the art-making process itself to be the work of art, has always been pronounced: his confluence of sound making and image making, for example, in 77 Million Paintings (2006), or his linked and simultaneous enquiries into the nature of bells and the cultural concept of time, as described by his Bell Studies… release of 2003. In this, Eno’s enduring radicalism as an artist lies in his ability to make the concept, process and product of his art entirely synonomous with one another. Aesthetics thus become the alibi for a questioning and rearrangement of process, which in its turn become the work of art itself. In relation to its context, such a method of art making has the capacity to be as disruptive as it is alluring - and hence achieves a latent political content.

There is at the heart of Eno’s fascination with the generative creativity a profound assertion of art’s capacity to celebrate and enhance the condition of human experience. “I am only interested” Eno has said, “in art that expresses and celebrates life.” And it is perhaps this notion of sentient being - of life’s progression through differing states, variations played to a common theme, fluctuating in consciousness - that Eno’s generative art most addresses, and which achieves such eloquence in his collaboration with Mimmo Paladino.

January, 2008