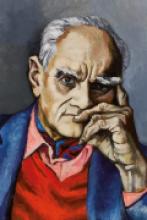

A conversation with Mimmo Paladino

by Federica Pirani

F. P. Has working in the Ara Pacis led, even if only implicitly, to you dealing with the theme of peace? Apart from anything else, the Pax Romana is very different to today’s notion of peace, alluding, as the root Pac (pactus, pactuare) suggests, to an agreement between humans beings and taking the form of an “absence of war”, or rather as the end of the war. Prosperity, well-being and the return of the golden age, well represented by the luxuriant acanthus flower clusters and by the female figure nourishing the twins depicted in the reliefs on the altar are the themes that inspire the ancient monument. Do you think that contemporary art still has, or could have, a significant role in this field?

M. P. Quite irrespective of the place we are in, I believe that by its very nature art embodies values of peace and that it represents a positive force. Art encourages reflection and a critical spirit. In tragic periods of war, on the other hand, humans do not think.

F. P. Richard Meier, who designed the Ara Pacis complex, has used light as a building material, taking visitors on a route organized according to different intensities of light. He also avoided using curved elements, considering “it to be impossible to trace any other curve in the presence of the large circle of Augustus’ Mausoleum”. Now the large aluminium circle that symbolically opens the show at the museum entrance, a multi-faceted geometric figure based on flat elements, a modern “mazzocco”, seems to engage with the architecture and the ancient sculpture. Reworking the favourite solid of Paolo Uccello, who transformed it into a fantastic headpiece for his painted knights, it seems that this work is posited as a threshold, an element of passage on which archaic signs and ancient sculptures appear.

M. P. This work, the large black circle, is inspired by Paolo Uccello’s “mazzocco”, a playful element that he adapted in headpieces for his figures, but also a warlike sign and an element of thought. I am fascinated by this ability to transform a geometric figure of study into a fantastic, fairytale-like image, even though I believe that at the heart of any artistic project there is always an element of logical, rational reflection. There needs to be a rational anchor, even if this is then undone by the brilliant intuition of different artists. This is where the quality of the work lies. The circle is covered with signs and graffiti, a recurrent theme in this exhibition. And indeed in the Ara Pacis Museum it is possible to find graffiti that tells us about and represents the different historic layers of the monument. It was also the first kind of sign left by humans on cave walls, a primordial gesture, a scratch on the wall with a stone. The work therefore dialogues with the contemporary architecture of Meier, and is very much part of contemporaneity. In my view, Meier’s architecture is not just a shell that enhances the chromatic and artistic qualities of the Ara, but a contemporary spatial creation that should be supported precisely because it is an incredible achievement in a city like Rome. It is the beginning of a co-presence of ancient art and contemporaneity that I hold to be a value in itself, quite irrespective of the outcry it has caused and of any individual assessment of the aesthetics and the quality of the work. The possibility that an artist, starting with my own experience, can engage with the historic space of the monument and above all with the contemporary sign of our civilization seems to me to be truly formidable.

F. P. In the case of the contemporary architecture that envelops the Ara Pacis, you chose to interact with the bright walls, producing a permanent work, the mosaic that gives onto the Lungotevere. Of all the various artistic techniques, mosaic is the one that, more than any others, mirrors and interacts with the changes in light and its reflections in the course of the day. On the other hand, for the exhibition you chose a different, more intimate, I might almost say holy space. Were you intrigued by the underground spatiality of the niche below the Ara?

M. P. The mosaic interacts with the light. The convex course of the mosaic surfaces for the Ara Pacis reflects the zenithal light. When I visited the space below for the first time, I was struck by the central “chamber”, which has a strange labyrinthine configuration and which in turn contains the small niche, a fulcrum beneath the Ara. In this space I positioned a sculpture produced some time ago. The figure is facing the wall with its back to the viewer, and protruding from its back are some tree branches. I used this work in an installation I did for an aqueduct in the Sannio mountains. It is evocative of a diviner, a human figure that searches for and discovers sources of water, but it is also, allegorically speaking, the figure of the artist who, every day, poses questions and seeks something.

F. P. I think the most interesting aspect of this exhibition at Ara Pacis, apart of course from the ineludable relationship with the site and the symbolic and historic significance of the archaeological monument, is the overall scale of the intervention. The different works can be contemplated individually. Each one, in fact, displays a particular aptitude for occupying its space and for catching the light. When considered together, however, they form the elements of a dialogue, of an initiatory itinerary towards the most sacred place, the niche below the Ara, the “secret chamber”. Appearing on the walls here, as if they have emerged in the wake of a shamanistic ritual, are archetypal signs and figures that need to be deciphered and interpreted. The whole work is conceived, then, as a single, complex installation that interacts with the spaces filled with the music of Brian Eno. What was the idea behind the choice of the different works, which together form a single, complex installation?

M. P. I view this work at Ara Pacis as a single, total work, as if one were looking at just one picture. That’s why I don’t want to hang any paintings on the walls. The whole work is conceived, imagined and even modified with respect to the original idea, above all on the basis of the space and also the requirements of Brian Eno, who will contribute his sounds and his concrete forms.

F. P. Time and memory, myths and artistic idiom are the territories traversed by these works, the most significant and unifying feature of which is the figural element. Filling one long wall are bodies curled up in a foetal position and casually bundled up between the aluminium grilles of labyrinthine wagons, prisons of recollection travelling along unknown tracks or trains of memories that force us to follow paths that have already been delineated. Alongside, hieratic Dulcineas with bark arms try to grasp the elusive love of the solitary knight; petrified sleepers or dreaming figures await the breaking of the spell, while in the centre, in the “house within the house”, metamorphoses of red signs appear on the walls and a diviner with magical branches searches for the hidden spring. All this is a synchronic cosmogony consisting of the remains of individual experiences and of others drawn from collective memories, archaic signs of the underground world together with morphemes from the history of art. Visiting the exhibition is not just about observing the works, but is also about experiencing a different, timeless space in which stories and legends that make human affairs aesthetically experienceable start circulating again.

M. P. The figure is a recurrent theme in this work. The one with human features is concentrated in the “casket” in the centre of the architectural structure and branches out in fragments over the walls. These traces derive from the film El Quijote, they are the remains of a scene depicting the burning of wooden statues and a horse. The scraps, the splinters that survived the fire were then cast, and are on the walls together with the graffiti.

F. P. For many years now it has seemed possible to discern in your work an enduring concern for the setting. Not infrequently you produce works directly on the wall, such as the graffiti at the MADRE in Naples or the mosaics at Ara Pacis and the Teatro Argentina in Rome, or else you create complex works where different expressive forms coexist: sculpture, painting, graffiti, installation, musical elements. It is likely that this tendency to operate on an environmental scale is something of a connecting thread that has led you to choose for your aesthetic inquiries works potentially designed to integrate with the urban architecture or with the natural landscape. I am thinking of I Dormienti, realized in 1998 for the Fonte delle Fate in Poggibonsi; or Una Piazza per Leonardo (A Piazza for Leonardo), the remodelling of the entrance to the new Museo Leonardiano in Vinci, which was completed in 2006; the Torre Ghirlandina in Modena; but also the extraordinary and now almost historic Montagna di sale (Salt Mountain) installation in Piazza del Plebiscito in Naples, which transformed a non-place into a theatrical and popular open-air space.

Is this the dimension you prefer for your works?

M. P. Thinking about it I have never been interested in works enclosed within the rectangle of the canvas, though I have of course produced lots of pictures. The crossing of borders has always been part of my practice. For example, the key idea of the emblematically entitled Mi ritiro a dipingere un quadro (I am retiring to paint a picture), which I produced back in 1977, is expressed more through the title than in the concrete nature of the work itself. It was a small oil painting, but it was inserted into and related to the architectural space of the gallery by means of a series of drawings on the wall. The roots of the work lie in Arte Povera and in Conceptual Art, because everything has some source of inspiration. No work arises from nothing, and despite the originality of individual expression, it is rooted in the history of art. A young artist in the 70s necessarily had to engage with a particular context and with previous lines of inquiry. Moreover, I have always had a great personal interest in the concept of space as geometry, as architecture. Even in a temporary work like the one I did for the Torre Ghirlandina in Modena, I expressed a playful, festive intention around one of the city’s symbolic monuments.

F. P. For this exhibition you are once again working with another artist, Brian Eno.

Has the shared aspect of the creative experience always been satisfactory? I’m thinking here of your work with Michelangelo Lupone, Brian Eno and Lucio Dalla, but also of the theatre sets with Mario Martone or your role as the director of El Quijote. Do you regard these encounters as a source of new stimulus rather than of potential conflict?

M. P. I’ve always been very interested in new experiences, in seeing what can happen when a poetic sign and a graphic sign, a musical and a pictorial sign are combined. It is not a question of thinking in terms of a juxtaposition, of adding together two elements, but rather of an entity that is the fruit of the coming together of two expressive forms, of a creative alchemy. I believe that this coming together also took place in the art of the past, for instance between the Baroque architect and the painter who produced an altarpiece. In my theatre experiences, for example, the people who have invited me to collaborate have almost never thought of my role as being that of a set designer. They invited a painter who could interact in the theatre space on the basis of ideas, convictions and a shared sensibility.

F. P. Your ability to lay yourself on the line also seems to persist in your experiments with different artistic techniques, in your investigation of various materials, which you share with master craftspeople and artists.

M. P. I have rarely collaborated with craftspeople who are stuck in their working ways. Ever since my work in print workshops with Giorgio Upiglio in Milan and the Bulla printmakers, or with the mosaic craftsman Costantino Buccolieri, I have found great craftspeople willing to call into question and to reconsider accepted knowledge and techniques. The first time I worked with Upiglio I had never produced a plate in my life. At first I was very hesitant, but then he himself urged me to use the acids freely, disregarding established rules and immediately putting me at ease; we both obtained unexpected results. Likewise with Davide Servadei at the Gatti Ceramics Workshop: when we throw sand from Stromboli or Sorrento coral into the kiln, the effects are often surprising. What with his technical expertise and my desire to experiment, we achieve results that are highly and mutually satisfying.

F. P. Do you think it is still possible to consider – or is it just an abstract Utopia – architecture and urban planning as the arts of modernity, within which aesthetic experience can spread in a democratic fashion? Some of your work in the field of design, for instance the Dulcinea lamp designed for Danese or the consideration you give to the work of an artist like Bruno Munari, seems to point in this direction.

M. P. There are moments when one see certain possibilities, as was the case with the lamp, a sculpture that gives off light, a piece of accessible, creative imagination that anyone can take home with them, an everyday object that is functional but also fantastic. As for Munari, I have been a great enthusiast of his work ever since I was at school. It is an everyday compendium for visual perception and a fine example of the playful dimension of aesthetic experience that I am particularly like. He made useless objects together with other very useful, practical, straightforward ones. He was the expression of the possibility of producing “democratic” objects, which was a complete novelty at the time. The idea that a chair, lamp or table of evident aesthetic qualities might end up in anyone’s hands was a massive step forward for the time. That’s what design should be all about. What’s more, certain contemporary art projects in unusual, unconventional places – a park or piazza, subway or archaeological area – can trigger a “short circuit”, involving a wide public in an original and unexpected aesthetic context, as happened with the Montagna di sale in Naples.

F. P. This “short circuit” also manifests itself at the Ara Pacis, where different languages, from the expanded circularity of Brian Eno’s music to your pictorial and sculptural images, and the clear geometry of spatial design enter into contact with the forms and figures of the classical world, erasing historic distance and recreating and renewing in a new epiphany the eternal present of art.