Necessity and beauty

by Ferdinando Scianna

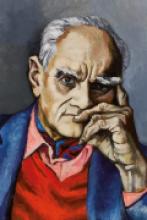

Accompanying Mimmo Paladino while he prepares a work or mounts an exhibition is always a rather special experience for me. Special because it stirs a complex tangle of stimuli: affection for a friend, admiration for the artist, the curiosity to observe the twists and turns of a creative process full of unexpected surprises, the intellectual satisfaction of feeling part of an incessantly exploratory line of inquiry which, when probing the implications of a site, spatial problem, light, word or suggestion, can change direction at any moment. Apparently chance developments invariably reveal deep, complex motivations and thought patterns and produce necessary results.

What intrigues and fascinates me most is the transformation of intuition into thought and necessity.

Necessity and beauty. Because Paladino is not afraid, as many contemporary artists seem to be, of beauty.

In short, a real pleasure for a photographer.

I followed the installation of the Ara Pacis exhibition almost from the outset.

Everything seems to proceed according to a pre-established project. Those magnificently dreadful burnt men facing the wall, the tragic fragments scattered over the long white wall were contemplated by Mimmo through a permanent haze of cigarette smoke. Aloof from the surrounding hubbub of the installers, his eye, brain and sensibility waited, watching for the signs that those objects would build up in relation to each other through a graphic fabric that would transform them into a single visual and narrative text that is different each time, as is the site where the artwork is produced, in a mix of graphic elements, sculpture, theatre and narrative. The long, dark train of iron, ceramics, figures, oneiric elements, pain, sand, different materials, memory, had already been installed in what seemed to be a definitive fashion.

But nothing is ever definitive in a Paladino exhibition.

We saw him moving constantly between one element and another, one spatial entity and another.

The next morning, as if the night had wrought a revolution, the train was moved to a completely different context of space and light. A move that immediately revealed itself to have been necessary and which helped me discover new images and connotations in the extraordinary well of implications and images contained in the work. The move meant of course that a whole wall and a whole space that had previously been occupied by the train were now empty.

‘What are you going to put here?’, I asked curiously. ‘We’ll see’, he responded, and then mentioned some vague idea about some large pieces he could retrieve from Paduli.

Naturally, when I returned a few days later to complete my photographic documentation work for the catalogue, I found something completely different and quite extraordinary: a whole fantastic wall of shoes and birds in which grace and the sense of unease aroused by what look like remains from an extermination camp blend together mysteriously.

It was all the more mysterious because this new presence engaged dialectically with the other pieces, enriching them and altering the sense of each individual element and of the show as a whole.

I also saw the sense of the “crypt” change several times. Here, for example, all it took was a small electric “accident” to reveal a fresh possibility to Paladino, which led to a reduction in the final intensity of the lighting and the creation of an emotional, red intimacy associated with a place of worship.

When I had last visited the large wheel was all wrapped up. Now I found it positioned triumphantly in front of the Ara, setting up a bold dialogue between its blackness and the white of the monument, the circle and the almost square structure of the altar. An object which also seemed to have just been extracted from distant memory to speak to us, with its clear-cut, indecipherable signs, of the language of a lost cult for an unknown god. In a word, it has been a lucky privilege to have taken part, as a photographer, in the adventure of that reinvention of the sacred which can still, though it happens rarely, be a work of art.