Ara Artis

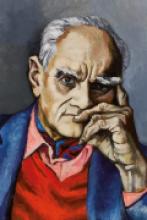

by Achille Bonito Oliva

Mimmo Paladino has organized his work for the Ara Pacis space by means of various curtains and scenes that simultaneously include minuets of the imagination, relations between objects resonant with anthropological memory and a more autobiographically obsessive memory. The scene is not governed by gravitational laws, or rather it acknowledges a visual centre of gravity in front of the altar and is represented by a sculptural “mazzocco” in black aluminium – which iconographically recalls Paolo Uccello’s Rout of San Romano – tattooed with traces of star signs. Like the ‘o’ of Giotto, but three dimensional, Paladino’s sculpture faces up, in terms of proportion, harmony and symmetry, to the whole Ara Pacis construction, serving as an introduction to the intertwining of expressive idioms and the interdisciplinary duet between Mimmo Paladino and Brian Eno that takes place on the floor below.

All the figures of the Neapolitan artist move according to individual points and trajectories, yet they are integrated within a single movement, that of an epiphanic image, of an apparition that connects the single parts in a dance step that moves towards a loss of weight.

If the curtain opens and closes simultaneously on the empty and full centre of the sheet, a two-part representation takes place around the edges. In the first the Baroque gaiety of elements such as trees inserted into the wall surrounds the lofty pause and a mass of leaves. In the second there is another pause in the centre, bodies and fleeing elements. The scene has the appearance and the consistency of an image filtered through the dream of the artist, which brings together in the temporal space of the image a narrative of figures and an abstraction of organic forms.

A state of vigil accompanies the other image, where the same artist establishes relations between

apotropaic objects and natural elements, masks and forms of everyday objects.

The state of vigil is what permits the calibration of the elements, a system of accord between the various parts and a distribution linked to mechanisms of memory. The work is traversed by the collision of a dual reference: one is to a primitive and archaic culture, the other is to a culture that is contemporary to the sensibility of the artist, who views the possibility of every fantastic co-presence as being contemporaneous to himself.

Paladino’s practice is marked by a painting and sculpting of surfaces, in the sense that he tends to visually foreground all the sensory data, even the innermost ones. The work becomes the point of encounter and of a clearly perceptible expansion of cultural motifs and of sensible elements. Everything is rendered in terms of sign and matter, traversed by different temperatures, hot and cold, lyric and mental, dense and rarefied, which appear through to the calibration of the colour.

For Paladino making art means having everything on the table in a rotating and a synchronic contemporaneity that succeeds in pouring into the melting pot of the work private images and mythical images, personal signs associated with individual history and public signs associated with the history of art and of culture. Such a process of traversal also means not mythicizing one’s ego, but rather inserting it in a collision course with other expressive possibilities, thereby accepting the possibility of positioning subjectivity at the meeting point between many joints, according to the definition offered by Musil: “Being and the delusion of many”.

The support is therefore a sculpture of surfaces, effected as a possible profundity. All the data of the sensibility are thus visually emergent, the site of transformation into the image of thin, impalpable motifs.

Signs of the abstract tradition, the matrix of which is the work of Kandinsky and Klee, and of more figurative traditions are interwoven in a single, organic motif.

The different temperatures of the sensibility condense mutually according to a bond open to free association. The rarefaction of every different temperature, mental and material, finds an appropriate place on the surface. Paladino tends never to declare his own biography, in that everything becomes sculptural motif. The geometry of the sign is immediately interrupted by the densification of figurative motifs that combine gently, without marked breaks in chromatic tone, with the rest of the composition, as in Miró.

The idea that supports the image, specially the pictorial one, is that of the fragment, of the detail that expands and hooks up with another detail. The state of mind that underpins the composition is the state of the total work, supported by a series of references to idioms drawn freely from the history of art, of the treatment of the surface à la Matisse. But the reference is always attenuated by an interior recovery of the data, inside like a sensorial temperature. The surface becomes the explicit threshold of the image, even when this seems to extend beyond its pedestal. The signs are ciphers that colour and decorate the skin of the sculpture.

For Paladino art is always a response to a lack, a practice imbued with the desire to compensate for and heal an initial gap. Art is on principle against any loss. Even if it forces its action into the mental system of negation, within the site of linguistic catastrophe. The rupture takes place here, yet shelter is sought within the decorous private room of language, where the irreparable is repaired and where the social system has placed exchange and the small manoeuvres of existence.

The art of Paladino, transpainting and transculpture, introduces a different kind of economy. Not simply a dual economy of debit and credit, take it or leave it, but an economy underpinned by a perfect dose of opportunism. This consists of excluding from the outset the possibility of a reductive choice, of a univocal gesture which, in its univocity, represents a taking away and a further loss.

Art acts deliberately upon irresponsibility, on the solution that excludes functionality and that introduces a possibility, a prospect of pleasure in which the gesture is not linked to an idea of paralysis or movement but rather to the simultaneous illusion of both possibilities.

Paladino has always created, as has all contemporary art, an ambiguous tension in which the manual and the mental coincide and develop a position where theory and practice, painting and sculpture, project and execution are not at opposite poles but are an integrated part of artistic activity.

Paladino has always woven around his work graceful fences of attention, deserts of shadowy sensibility capable of generating a contemplative gaze different to the everyday gaze. The sword that cuts this different attention is the magic moment in which art, in this case transculpture, is also posited as the gold measure of all matter and of every possible form, a “train” that transports an ossuary of anthromorphic forms ranging from iron to terracotta.

Here the nature is that of art, which does not envisage orders, gravitational laws or obligations, but freely arranges its elements as in the primitive space of the feast, where there is no high or low, no horizontal or vertical, but everything is arranged according to a docile circularity that it seconds with presence, simultaneity and an absence of hierarchies: paint and coal on the wall, a “sleeper” in terracotta and a mast-like silhouette fixed on the wall listening to time.

Paladino’s painting and sculpture become the theatre of a multiple apparition in which every evocation and every voice acquires the force and the consistency of the image, in which every absence is transformed into figurable presence, capable, that is, of representing and alluding concretely but without arriving at the point of exhausting meaning. Because there is no meaning, in that there is no narrative.

All that exists is the epiphany of matter, which expels forms and symbols lying inside it, beneath the skin of matter itself. Transculpture is inscription upon the skin of matter, on its surface, of what lay inert and at the same time urgent in its underside, but without this happening in a dramatic fashion.

Reversing every gravitational law, Paladino arranges matter on an inclined plane, seconding the rolling of forms, the clotting of images through their shifting from a state of shadow to a state of thickness, according to the evidencing procedure of sculpture.

The artist, therefore, is the person who seconds the inclinations of the material by means of a process of intensification capable of conferring transparency on what has thickness and opacity. Everything becomes extremely explicit, every form seconds its own inner urgency. Because formlessness does not exist in art: every indistinct flux always acquires its own clearly individual appearance.

If anything form acquires an elaborateness of its own, a radiating potential capable of covering multiple references. And so the sailor becomes the warrior, the boat a shield, the oar a spear. Hair becomes algae and the plain of small forms becomes land. Transculpture is the theatre of silent metamorphoses grasped in their seamless transition from one state to another.

Paladino, then, reintroduces surprise, the modification of matter that transmutes from inertia to movement, from the disarticulated to the distinct state of form. He has coagulated the transmigration of forms in the material of sculpture, respecting in any case the internal rhythms of their continuity with the light and ferocious hand of someone who wants to inscribe on the skin of metal the sign of the soft geometry of Mediterranean memory, made up of incandescent temperatures yet softened by the consciousness of the loss of origin, of the impossibility of fully recovering the birth of things. The greatness of current art is that it cannot evoke but only invoke. This is the secular religiosity of the Transavanguardia.

In the sphere of spirituality there has already been an encounter with Brian Eno, an exchange between art and music. Now another one is taking place in the myth-filled space of the Ara Pacis in Rome. The English musician has also produced an installation in the various spaces, consisting of twenty portable radios and small speakers set into the ceiling. These emit a musical fluid that drags along with it a horizontal sense of time, a fragmented and at the same time liquid flow of details of concrete life, voices and murmurs that reference an entirely oriental dimension.

A short circuit of complementary sensibility is triggered between Mimmo Paladino and Brian Eno, with the former bringing with him the whole Western tradition, ranging from Lombard, Gothic and Baroque sculpture to the historic avant-garde movements, and the latter in turn contributing a sensibility associated with the history of concrete music, which starts with Cage and is steeped in an oriental tradition of sound.

In this way it seems that the interweaving between East and West has the capacity to liquify the image in music, and that in turn sound is concretized in iconography.

Ultimately, the vaporization of sound in the spaces of the Ara Pacis creates a contact between the classical memory of the marble figures of the Roman monument and the painting and sculpture of Paladino.

In its structural horizontality, the music of Brian Eno beats a circular time that envelops everything and produces an ardour where there is no longer a historic distance and the history of styles but the almost non-temporal formation of an eternal present of art and of the coexistence of different expressive languages.

In this way the Ara Pacis is transformed into a house of art, Ara Artis.